Lesson number 100 – although it’s an arbitrary milestone, it’s a milestone nonetheless that’s taken 7 years to get to. Starting this blog site in 2017, my intention was to offer up a diary-like set of lessons that discuss various topics that I found interesting related to finance and investing. I’m not a finance professional and I don’t have a niche finance related designation, but the areas of investing and finance are themes I have always found very interesting, have attentively researched, and successfully put into practice to manage my own wealth. My subscriber base is small, many of which are probably my friends who may have subscribed out of pity or reluctance. Either way, I hope that whoever has read any of the lessons over the seven years has gained some value from the content, because that’s always been my goal over anything else.

For this “milestone” of a lesson, I thought it would be fitting to do something similar that I did for Lesson 50, and that is to recap several investing mistakes that I have done over the years, and focus on the key lesson themes that came out of each mistake event. While I have made my fair share of mistakes, I decided to choose 3 key events that I believe have really shaped my investing philosophy and how I think about risk, asset allocation, and overall long term investing. I’ve also included a bonus entry about option trading that I think many retail investors fall victim to due to a lack of understanding around the risks involved. Let’s begin!

Event #1 – TSX Index Correction in 2014 followed by Canada Economy Recession in 2015

Key Themes: Portfolio Diversification, Risk Management, and Reliance on Historical Performance to Predict Future Performance

Past Lessons That Cover Key Themes:

Lesson 32: Funny Money

Lesson 41: Risky Business and Puerto Rican Madness

Lesson 71: Filling Your Tool Belt

Lesson 78: First Steps with ETFs

Lesson 93: Breaking it Down

This was my first real taste of what the stock market consists of regarding risk. I first started investing in the stock market in 2013, where at the time, the TSX had been in a pretty consistent bull market since the 2009 Great Financial Crisis (GFC). I knew nothing about stocks, and had only invested in what I knew up to that point, which were risk free GICs paying sub 3% annual interest at my Servus Credit Union bank. I was eager to learn and start investing in stocks right away, so I did what I thought any rationale newbie to stocks would do – look at what had done well in the past, and buy it. This isn’t the absolute worst strategy, but at that point, the oil and gas sector had done quite well, and being a major component of the TSX, so had the TSX index up to that point. By the end of 2013, my portfolio consisted of ~90% oil and gas stocks – Tourmaline Oil (TOU), Enbridge (ENB), Suncor (SU), Birchcliff Energy (BIR), Gibson Energy (GEI), Keyera (KEY), TC Energy (TCE), and maybe a few others I can’t recall. I mean why not, these stocks were all on fire over the last few years, so I figured it was a no brainer to own them for the foreseeable future… why wouldn’t it perform as well in the future as it had done for the last 3 years? And you know what, at first, the stocks performed great, and I remember thinking “wow, investing in stocks is so easy”.

Figure 1: Energy Sector Company Stock Charts Aug 2024 to Jan 2016

Ouch – what a painful way to learn about diversification. But I did learn, and learned very quickly, the importance of diversification and the folly of solely relying on past performance to predict future performance of a stock. Now many of us don’t have the time, interest, or knowledge to study a business at length and develop an opinion on its financial future. But if you are self managing your investment portfolio and doing the research, you should understand the risk of assuming that past performance of a stock is a representation of how it will continue to do in the future. It may or may not hold true, but it doesn’t have to – that is important to understand. This goes hand in hand with diversification. Having all your eggs in one basket is not a prudent way to invest. It isn’t uncommon for only a handful of stocks to drive the performance of your entire portfolio. This is actually the case for general stock markets, where only a handful of companies can drive the market in a particular direction for a sustained period of time. This is due to the market cap weighted nature of most indices (larger cap companies will make up more of a portion of the entire index than smaller companies will). I don’t think there is a fool proof answer for what diversification should look like within one’s stock portfolio, but having exposure to multiple companies across a few different industries will help manage risk and smoothen the performance curve over the long run, even if it means underperforming the index sometimes. For most folks, simply owning index ETFs helps mitigate this risk the easiest.

Event #2 – Concordia Health Care Collapse in August 2016

Key Themes: Portfolio Weightings and Risk Management

Past Lessons That Cover Key Themes:

Lesson 50: Instant Replay

Lesson 71: Filling Your Tool Belt

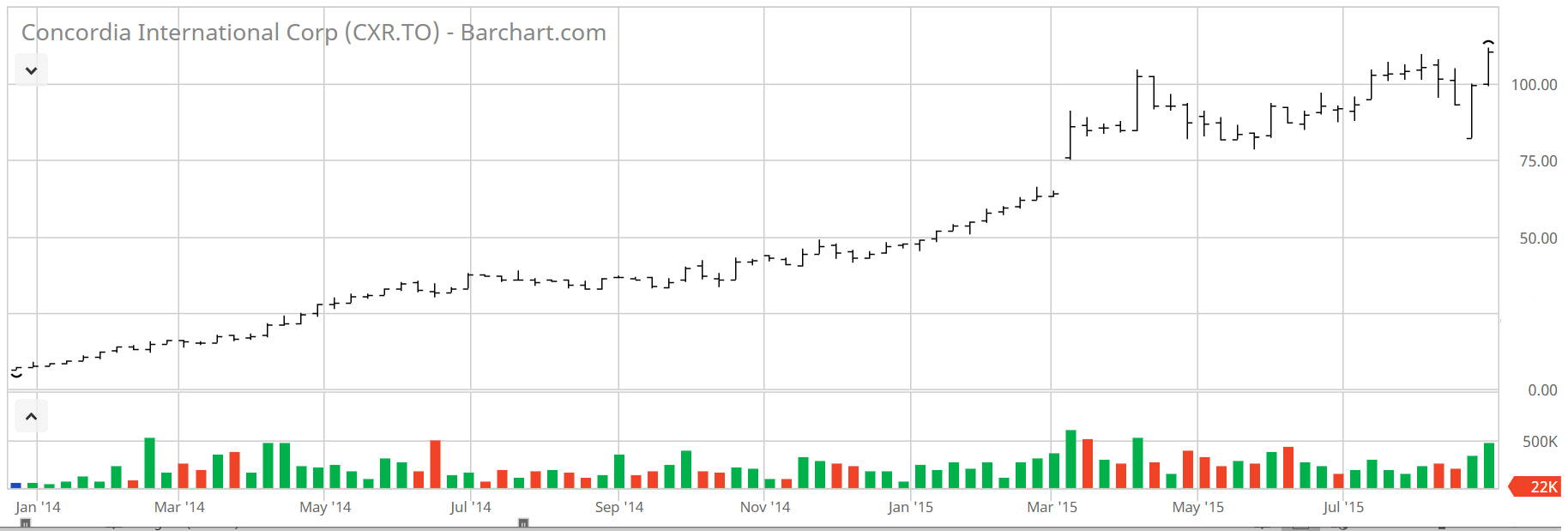

This investment will forever remain entrenched in my brain because the financial loss from it, from a percentage basis, was one of my worst experiences since I started investing. Concordia Health Care was a Canada pharmaceutical company that I started investing in at the start of 2015 (CXR was the ticker at the time), and it went on an absolute tear into late 2015. With the spanking I received from 2014 still fresh in my head, my portfolio was now more diversified since then, and my investment acumen and financial analysis skills were improving. I enjoyed reading financial statements and analysing various metrics to help inform me whether a company was worth buying or not. Concordia’s balance sheet looked amazing and fit all of my criteria – low current and forward P/E ratios, ROE exceeding 25%, reasonable leverage ratios, consistently high growing EPS, revenue, and net margins, and a consistently growing stock price fueled by a debt heavy M&A spree. Concordia’s largest acquisition happened in 2015 with its purchase of Amdipharm Mercury Limited (AMCO) for $3.3B. I kept buying more and more of CXR based on its attractive valuations and fundamentals, and by Q3 2015, it had grown to about 25% of my entire portfolio. Then, in late Q3 of 2015, came the shit storm (I covered this event in length in Lesson 50, so I’ve reused content describing the fall out below).

Figure 2: CXR Performance Jan 2014 - Sept 2015

First off, the big AMCO acquisition roughly doubled Concordia’s current market capitalization, and required significant levels of debt and equity financing which included various forms of bank facilities, senior notes, and issuance of common shares. Shortly after the acquisition, questions began circulating amongst analysts and institutions tracking the stock about Concordia’s ability to afford its cost of capital at its current debt levels, and whether or not its current level of cash flow was sustainable to meet current debt obligations and covenants going forward.

Around the same time as the AMCO acquisition, Concordia reported its Q3 2015 earnings which slightly missed analyst’s expectations. At the same time, the Valeant Pharmaceutical (VXR) scandal had begun to unravel, and questions around unfair drug pricing in the pharmaceutical industry began surfacing. Favored US presidential candidate at the time Hilary Clinton had made several comments about the need for stricter drug pricing regulation which she would surely implement under her future presidency once she got elected into office.

The stock began to tank, and my once beloved invincible stock began to deteriorate. So what did I do? I bought more and lowered my dollar cost average into the stock.

In the coming months leading into 2016, news continued to come out around Concordia’s inability to afford its cost of capital, its inefficient capital structure, as well as criticism around Concordia’s unethical accounting revenue recognition tactics to misstate earnings higher than reality to make the company look undervalued. The stock price continued lower through 2016 with the constant negative downward pressure on the pharmaceutical sector from political leaders and iconic short sellers. I eventually sold the last of my position for $21 per share in Q1 2016. My dollar cost average price for CXR was around $63 per share. The resignation of the CEO followed, allegations and lawsuits arose around Concordia’s accounting practices, and speculation persisted around whether the best interests of shareholders were upheld through Concordia’s M&A activity over the last several years.

What a roller coaster ride. Not only did I sell this stock at a huge realised loss exceeding 50%, but it had made up a large portion of my portfolio from late 2015 to early 2016. I don’t ever blame myself for having owned CXR as I was basing my decision on publicly available financial information which I can only assume to have been true. What I do blame myself for is falling into the same lack of diversification trap that got me into trouble in 2014. There are investors out there that invest with conviction in a stock that they really like and truly believe in. I get that, but it’s also important to understand the amount of risk that playbook comes with. Having 90% of your portfolio invested in NVDA since late 2022 will have made you look like a genius, but it doesn’t mean that this was a smart or prudently risk managed strategy. Having 25% of your portfolio in one company means different things depending on how many companies you own. If your strategy consists of only owning 5 companies, then a 25% weighting in any one stock is normal. This, however, was not my case, where I owned a total of ~20 companies, and one of those was CXR which comprised of 25% of my total portfolio value. Not smart. I didn’t understand the risk, and I only forecasted what I wanted to happen without considering the risk that any one stock could attribute to my overall portfolio, especially one that I was overweight in. Needless to say, I underperformed the TSX in 2015 and 2016 as a result, feeling very humbled once again by Mr. Market.

Fun fact - Concordia was relisted as Advanz Pharma in November 2018. As of March 27, 2020, Advanz Pharma's limited voting shares are no longer traded on any stock exchange after being delisted from the Toronto Stock Exchange. Wow that is brutal.

Event #3 – Purchase (June 2016) and Sale (April 2021) of my First Home

Key Themes: Real Estate Leverage and Sufficient Down Payment

Past Lessons That Cover Key Themes:

Lesson 54: The Real Home Owners of Defactoville

Lesson 90: Factoring Permanence Over Fad

I truly believe it’s hard to have an opinion on real estate investing until you’ve actually owned real estate at least once. I have perhaps a less popular opinion on real estate investing, but I’ll set that aside for another time as I go through this event.

I’ve owned two real estate properties up until now – a downtown Edmonton condo from June 2016 to April 2021, and a townhouse in central Houston from July 2021 to July 2024. I want to focus more on the Edmonton condo purchase, but my lesson theme can apply to any real estate investment/purchase. I purchased the Edmonton condo in mid 2016 with a 20% down payment, and a fixed interest rate below 3%. This was arguably near the peak of the downtown condo market boom in Edmonton, especially condos that were considered more luxury or high end. Following the summer of 2016, a glut of condo supply followed (both for rent and for purchase), and coupled with the Canadian economic recession in 2016, condo values fell for the next several years. It didn’t bother me too much, because realistically it’s impossible to time the real estate market on when it’s “best” to buy, and at the same time, I also wanted a place to live. However, the fall of my condo value really hit me when I was going through the process of relocating to Houston for work, and as part of my relocation package, I was offered to be bought out of my mortgage at market price, and topped up on any equity loss I would have sustained. Well this couldn’t have worked out any better for me, and it was pure luck and opportunity that I managed to sell my condo at a net zero loss. I was bought out at market value which was ~20% less than what I paid for it in 2016, and then subsequently made whole on the equity loss.

Imagine that – selling a real estate investment that you’ve been paying a mortgage on over 5 years that had fallen 20% in value since first buying it. If the down payment and principal paid over that 5 years amounted to less than 20% of the initial purchase price, a seller would be underwater and would actually have to owe the bank lender the shortfall. Although I didn’t actually experience this scenario myself, my condo selling experience really highlighted the risks of small sized down payments (overleveraging) on real estate investments.

I was god damn lucky to get my purchase price (book value) back, and I was essentially able to treat my condo like a bond over those 5 years. If I didn’t move to Houston and take advantage of this relocation perk, I may very well still be living in that condo, or have moved somewhere else and have realised a massive loss on the condo, which would have severely limited the capital I would’ve been able to pull out and put into my next real estate purchase. It’s understandably more difficult for young people to buy their first home these days, and that’s reflected in the historical trend of cost of living outpacing wage growth. Therefore, more and more new first time home buyers are either waiting later in life to purchase, never purchasing and only renting, or purchasing on higher degrees of leverage. Purchasing on higher degrees of leverage is a benefit of real estate investing, but it also brings a lot of risk. It’s the same with trading on margin in your investing account, and it’s why brokers have margin requirements that every account holder must meet when trading on margin. If someone puts 5% down on a $500,000 home, it only takes a small 5% swing in home valuations to completely wipe out the home owner’s equity if they were to sell. That’s not a lot of margin for risk. Home prices rise and fall with the local economy, and home owners can’t always precisely plan when to buy or sell their home or real estate investment. Small sized down payments accepted by lenders was one of the main drivers for the 2009 GFC, where many people foreclosed on their homes at a net loss while still owing money to the lender. I proceed with extreme caution when seeing people I know investing in multiple properties on minimal down payments, because I don’t believe they truly understand the risk involved with extreme leverage on illiquid (and arguably ill-diversified) assets. I won’t pretend that I am a master real estate investor, because I’m not, as reflected by my condo purchase and sale. However, folks need to understand the risks involved when purchasing a home with whatever degree of leverage they are using, because these risks typically don’t materialize until it comes time to selling, and choosing to sell isn’t always a planned or desired endeavor at the time.

For what it’s worth, I think owning a space in the sky (condo) is not nearly as lucrative as owning land (house). Land is what appreciates and drives up home valuations over the long term. If you want to live in a condo, just rent it – let the landlord deal with the headaches of special assessments, anemic property valuations, condo board meetings, building maintenance and security issues😊.

General Discussion: Naked Call Options Writing / Selling Short

Key Themes: Risk Management, Leverage and Margin

Past Lessons That Cover Key Themes:

Lesson 50: Instant Replay

Lesson 59: Ten Baggers

My guilty pleasure is derivative trading. There I said it. I do it separately from my main portfolio, and although I always advise against it for most investors (especially new investors), I personally enjoy it. I love the mechanics behind derivatives, and I love the leverage you can extract out of it for short term speculative trading as well as for longer term investing. Having done derivative trading for years now, I have become very good at managing the risk that comes with it and limiting potential downside. I think risk management is crucial to understand and execute when trading derivatives, which unfortunately I believe to be a rare occurrence amongst many retail traders. Options are seen as ways to swing for the fences and get rich quick without understanding the downside risk that comes with it. I could talk about this topic at length, and how I think options should be traded, but we would need another century of time to cover it. Instead, I’ll focus on a key theme that I think many retail investors overlook when wanting to dive into options.

The theme is leverage and margin. They go hand in hand and I’ve already touched on this a little bit above. As with any financial instrument, there are limitations around how much debt you can expose yourself to when investing and using leverage. Like buying a house, you can put down a 20% down payment in order to take control of and “own” the asset. You can also put down 50% and still take control of and “own” the asset. Both scenarios give you control and ownership of the asset, but one requires way less capital. Option trading allows for extreme amounts of leverage to get exposure to the price swings of the underlying asset. Therefore, a 5% price swing in a stock produces a much more amplified price swing of an option of that same underlying asset. It works on the upside and downside.

Naked option selling/writing/shorting refers to selling option contracts against the underlying asset without actually owning the underlying asset. Let’s say I sell an option contract today on December 8th obliging me to sell you a widget for $100 (the strike price) on December 20th (exercise or expiration date of the contract). I make the premium or fee on this contract that you pay me. I don’t actually physically own that widget, so I am selling this contract to you “naked”, as opposed to “covered” if I did actually own the widget. I’ve just described selling a naked call option. Selling a naked put option is if I were to sell you a contract obliging me to buy from you a widget at a specific price on December 20th. I’m going to focus on naked call option selling only because these bear a ton more risk than naked put option selling.

If December 20th rolls around and the widget trades at $150, I have to go out and find a widget on the market and buy it at $150, and then sell it back to you for $100. I’ve just lost $50. The problem with selling this contract naked is that in theory, the maximum price that a widget could trade for is infinity – there is no cap. As a result, my downside risk is unlimited (whereas for naked put option selling, your downside is capped since the lowest an asset price can go is to $0). Imagine having to go out in the market and buy a widget at a much higher price such as $1,000 and then selling it back to you for $100 as specified in our contract. What if I didn’t have $1,000 lying around to buy this widget at market price on December 20th? I am absolutely screwed!

Here in lies the problem with selling naked call option contracts. Although I used a very exaggerated example using a widget, this blow up of an investor’s account due to naked call option selling unfortunately happens all the time during volatile periods of an underlying asset. An asset price can in theory go up to infinity, and because brokerage accounts will have margin requirements, losses will be capped as an investor will be forced to sell their underwater position when these maintenance margin levels are hit.

So why the hell do investors sell naked call options then in first place? Some view it as a way to generate additional income in their portfolio without having to put up large amounts of capital. The strategy typically involves selling call option contracts at strike prices far above the current underlying asset price. While this may seem like a low-risk endeavour, it only takes one volatile period where the underlying asset price jumps way above the contract strike price for the investor to be forced to close their position to maintain margin requirements. There are countless examples of prominent fund managers who get carried away with strategy, only to have their managed investor accounts blow up when the underlying asset of one of their naked call option short position spikes in price, forcing the manager to liquidate the now underwater naked option position to maintain margin requirements. This often triggers a short squeeze event in the underlying asset, where buying volume spikes as short positions are forced closed.

Don’t be fooled by this seemingly risk-free strategy to make “easy” income in your portfolio. If you have any understanding of options at all, at the very least execute a bear call spread to limit downside, or just steer clear of naked call option writing altogether.

Fun fact - I learned the pitfalls of naked call option writing the hard way, with the worst trade losing around -1000% of the original option premium I received from selling the contract. Needless to say, it’s been a long time since I’ve sold call options naked, and I don’t plan on restarting either any time soon.

Well there it is. A complete opening into the world of my most influential investing mistakes and experiences that have greatly shaped how I view risk and manage my investments today. I hope you are able to take away some learnings from these lessons, or at the very least, appreciate the cover photos I take myself for each lesson that I post. 2024 has been a fantastic year for stock market investing, and although it’s easy to feel smart and overconfident in a bull market, it’s the longer-term view for your investment portfolio that will make you a sure winner.

Let’s continue making sense of making cents (and dollars) in 2025.