A lot of what happens in investing has to do with human emotions and how that impacts decision making. Markets are never perfect because human emotion is involved, and that is difficult to predict. This is what causes mispricing of assets, arbitrage opportunities, and oversold and overbought market conditions. This of course can be extended to other areas of life outside of investing, such as consumer behaviour, policy decision making, economics, and social interactions.

As much as I am exhausted from talking about tariffs over the last few weeks already, watching how countries have been responding to US tariff threats in 2025 has brought me back to the days of learning about game theory in university economics courses, and how applicable this strategy has been in recent light of such global tariff activity. Let’s dive right into the principles of game theory, specifically the “Prisoner’s Dilemma”, and how it can apply to finance and investing.

The Prisoner's Dilemma is a fundamental concept in game theory that illustrates the conflict between individual and collective interests. This paradox demonstrates how rational decision-making by individuals can lead to suboptimal outcomes for all parties involved.

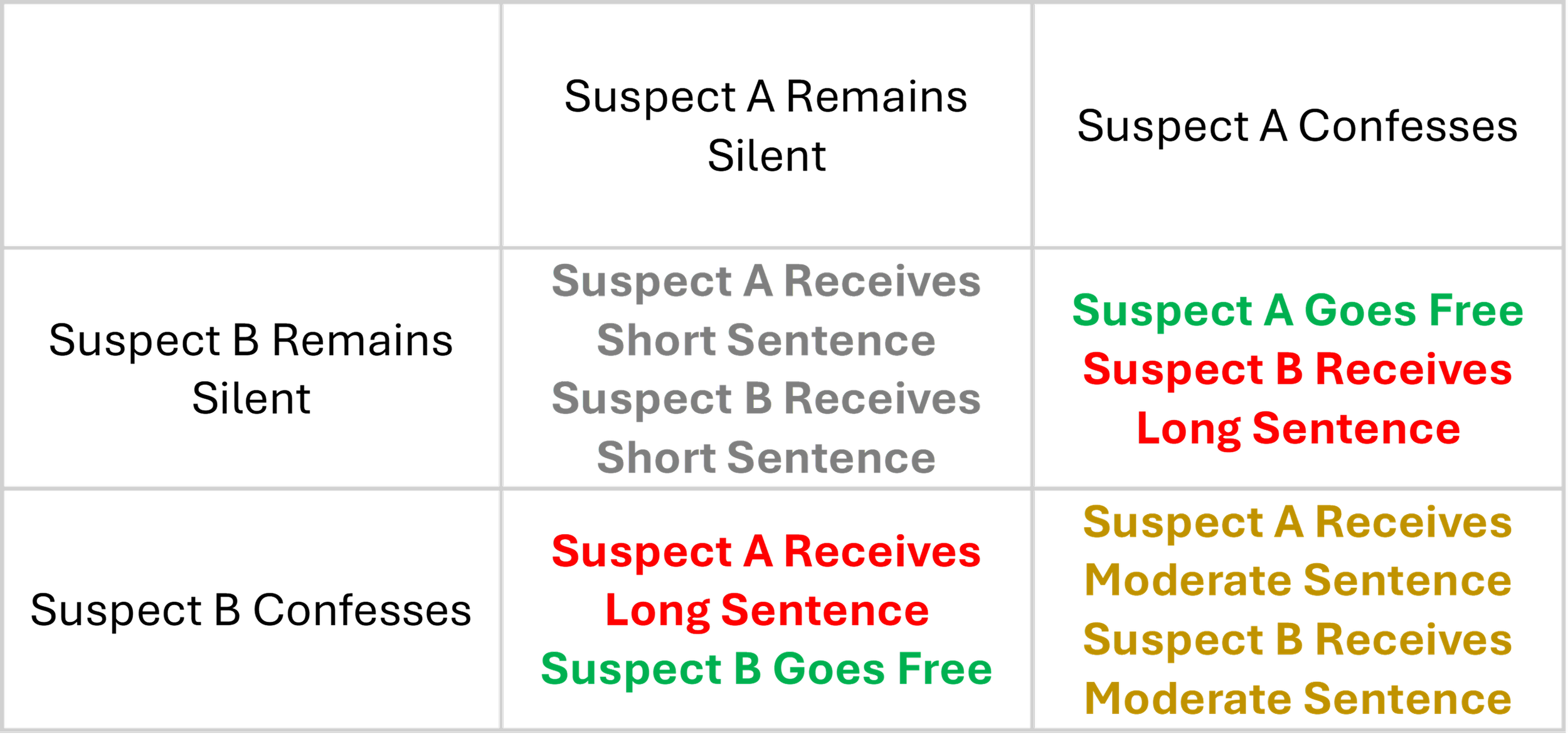

In its classic form, the Prisoner's Dilemma involves two suspects who are separately interrogated for a crime. Each prisoner has two choices: confess or remain silent. The outcomes depend on the combination of their decisions:

If both remain silent, they each serve a short sentence.

If one confesses and the other remains silent, the confessor goes free while the other receives a long sentence.

If both confess, they each receive a moderate sentence

The dilemma arises because each prisoner's best individual strategy, which is to confess and go free, actually leads to a worse outcome for both when compared to mutual cooperation, which is to remain silent and receive a short sentence. Two rational, self-interested individuals might choose to act in a way that is detrimental to their collective outcome, even when cooperation would be beneficial. This self-interested rationality over a collective mutual rationality for problem solving is the essence of the Prisoner’s dilemma.

The Prisoner's Dilemma offers valuable insights into financial markets and investment strategies in a number of ways:

Market Competition: Companies often face situations similar to the Prisoner's Dilemma when deciding on pricing strategies or whether to enter new markets. Cooperation might lead to better overall outcomes, but the temptation to undercut competitors for short-term gains can result in price wars and reduced profits for all.

Investor Behavior: During market volatility, investors may face a dilemma between holding onto their investments (cooperating with market stability) or selling quickly to avoid potential losses (defecting). If many investors choose to sell, it can lead to a market crash, harming everyone's portfolios.

Corporate Governance: Shareholders and management might face Prisoner's Dilemma-like situations when deciding between short-term profits and long-term sustainability. Choosing immediate gains might benefit some stakeholders but could harm the company's long-term value.

Risk Management: Traders often need to balance between sharing information for collective benefit and keeping valuable insights to themselves for personal advantage.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma concept extends beyond finance too, appearing in various aspects of our daily lives. Consider these examples:

Environmental Conservation: Individuals face choices between personal convenience (e.g., using disposable plastics) and environmental protection. While collective action would benefit everyone, individual self-interest often prevails

Traffic Behavior: Deciding whether to let someone merge in heavy traffic or to speed through a yellow light are everyday examples of the Prisoner's Dilemma in action

Social Media Usage: Sharing personal information on social platforms can provide immediate benefits but may lead to privacy concerns if everyone overshares

Group Projects: In academic or professional settings, team members must choose between putting in maximum effort for the group's benefit or minimizing their own work at the expense of overall quality

Doping in Sports: Athletes face the dilemma of using performance-enhancing drugs, knowing that if everyone does it, the advantage is nullified while health risks remain

While insightful, the Prisoner's Dilemma does oversimplify market realities. There are multiple interactions in real public markets daily, which involve repeated games where reputation and reciprocity influence decisions. Investors and traders can have very different and nuanced strategies, where they often blend cooperation & defection (i.e. partial position closing) rather than binary choices. There are also behavioural factors that come into play such as herd mentality and fear that often override rational self-interest assumptions. Any framework that attempts to predict market movements will always remain constrained by market complexity and human psychology.

Using the Prisoner’s dilemma concept can help to form one’s own opinions about macroeconomic activity, and assess overreactions to company news release (like earnings reports) and other market news in order to strategically make timely investing decisions. Using this concept is also helpful to assess current events like the recent tariff threats from the US to its international trading partners, and how potentially harmful a continued trade war could be, both in the short and long term, to all parties involved.

By being aware of this concept, we can strive to create environments that encourage cooperation and mutual benefit, whether in investment strategies, business practices, or everyday interactions. Ultimately, the Prisoner's Dilemma teaches us that sometimes, what's best for the individual in the short term may not be best for everyone—including that individual—in the long run.

BONUS CONTENT: Okay so this is more of an Appendix to the main body above, but I’ve included a few more detailed real-world applications of the Prisoner’s Dilemma related to market competition and financial markets.

Appendix A: Market Competition Examples

In situations where companies must make strategic decisions that impact their competitors, prisoner’s dilemma can arise. Here are some notable examples:

Advertising Expenditures

One of the most commonly cited examples of the Prisoner's Dilemma in business is advertising, especially in industries with fierce competition. For instance:

Cigarette manufacturers in the United States (when advertising was legal) had to decide how much to spend on advertising.

The effectiveness of one company's advertising was partially determined by its competitor's advertising efforts.

If both firms advertised heavily, their efforts would largely cancel each other out, leading to increased costs without significant benefits.

However, if one firm chose not to advertise while the other did, the advertising firm could gain a significant advantage.

This scenario created a dilemma where both firms might be better off reducing advertising, but the risk of losing market share to a competitor who continues to advertise creates an incentive to maintain high advertising budgets.

Pricing Strategies

Another classic example involves pricing decisions, particularly in oligopolistic markets:

Consider two major competitors like Coca-Cola and Pepsi.

Both companies would benefit most if they cooperated and set high prices, maximizing industry profits.

However, each company has an incentive to "defect" by lowering prices to gain market share.

If both lower prices, they end up in a less profitable situation for both companies.

For example, if both maintain high prices, they might each earn $10 million. If one lowers prices, it might earn $12 million while the other earns only $7 million. If both lower prices, they might each earn $9 million.

New Product Development

Companies often face Prisoner's Dilemma-like situations when deciding whether to invest in new product development or technology. The dilemma arises because:

Investment in R&D is costly and risky.

If one company invests heavily while others don't, it might gain a significant competitive advantage.

However, if all companies invest heavily, they may end up in an "arms race" that increases costs for everyone without providing a clear winner.

Cartel Behavior

Members of a cartel (although often illegal) face a multi-player version of the Prisoner's Dilemma:

Cooperating means adhering to agreed-upon price floors or production limits.

Defecting means secretly undercutting prices or exceeding production quotas.

While collective adherence to the cartel's rules benefits all members, individual members have a strong incentive to cheat for short-term gains.

These examples demonstrate how the Prisoner's Dilemma framework can help business leaders understand and navigate complex competitive dynamics in various industries and decision-making scenarios.

Appendix B: Financial Markets Examples

Individual traders' rational decisions often lead to collective instability, despite potentially better outcomes if participants cooperated. Here's how the paradox plays out across market dynamics:

High-Frequency Trading (HFT)

HFT algorithms prioritize speed over collective stability, creating a modern market dilemma:

Cooperative scenario: HFT firms could collectively provide liquidity and stabilize prices.

Defection scenario: During market stress (e.g., adverse news), HFTs rapidly sell positions to minimize losses, exacerbating price declines. While individually rational, this "race to the exit" can trigger flash crashes that harm all participants

Insider Trading

A multi-player dilemma emerges when traders possess non-public information:

Ideal cooperation: All traders preserve market integrity by not acting on insider knowledge.

Temptation to defect: If some traders exploit the information for profit, others face pressure to follow suit to avoid losing competitive advantage, eroding market fairness

Momentum vs. Contrarian Strategies

Trend-following creates self-reinforcing cycles with unstable outcomes:

Momentum trading (cooperation): Traders collectively sustain bullish/bearish trends.

Contrarian defection: Early profit-taking by some traders can prematurely reverse trends, causing losses for momentum followers. This mirrors the dilemma's suboptimal equilibrium

Technical Trading Arms Race

Widespread use of technical analysis creates a collective trap:

Cooperation: Reduced reliance on chart patterns could stabilize price discovery.

Defection: Traders overuse technical signals (e.g., moving averages) to front-run others, increasing market noise and volatility. This "pattern chasing" makes markets more unpredictable for all participants

Bull Market Coordination

In rising markets, traders face a temporal dilemma:

Hold (cooperate): Collective restraint extends the bull run.

Sell (defect): Early sellers secure gains but risk triggering a broader sell-off. The 2020 market volatility exemplified this, as panic selling during COVID-19 erased $9 trillion in global market value within weeks